Lake Sonfon was unusually dry for this time of year. The usual crystal clear lake, by this time of year, would have water lapping gently on the green, lush grass that embroidered its edges. The lake usually projected fertility, vitality, and serenity. Different species of birds, too many to name and a vast number of insects could be seen at all times, hovering and basking on the lake’s surface. Gold nuggets and other precious minerals lay embedded in the lake bed and were sometimes found on its edges too. During the day, the sun created a golden aura on the mirror-like lake surface. This phenomenal natural picture was only rivalled at night by the moon reflecting on its smooth surface in all its luminous quality, portraying a portrait of a spherical silver world. Lake Sonfon, on the other hand, had recently become a mere shell of its former self. The water level had gone down drastically, and the lake was no longer crystal clear, but rather muddy brown. The colourful collection of animals that had once made it their habitat had disappeared along with it. The lake now emitted a miasma of despair. People who live near Lake Sonfon said that the spirits had left the land, taking with them their good fortune.

Kabala village was about sixty kilometres from Lake Sonfon, and it, too, felt the pinch, the void left by the spirits. The rebel war had ravaged the peaceful village, and it was said that the atrocities committed by the rebels had driven away the spirits from the land. Everyone had their version, everyone had their beliefs, and everyone thought their version of events was correct. The midday sun shone through the sky, its golden rays beating down on the scorched earth. A rickety truck that had seen better days rolled through the cracked earth, leaving dust in its wake. It came to a halt, its engine sputtering and thick black smoke trailing from its exhaust pipe. It was Pa Thomas, the old man who delivered fruits, vegetables, gallons of water, and other items to the village at the start of every week. The terrible drought meant that no crops grew on the scorched earth. People in Kabala had to get supplies from Port Loko in order to be able to live well.

Pa Thomas came down in his rickety truck and leaned against the side with his arms folded. He looked around as he waited for the villagers to finish bringing down their supplies from the back of his truck. He was a wise old man. The years had come, firmly marinated in experience. He knew what people said about the drought on Lake Sonfon and the surrounding land. They blamed it on the absence of the spirits. He could not help but chuckle. Other areas were lush with green. What was it about these areas that was so different? Had their spirits not decided to go on vacation? The answer to what was wrong with Lake Sonfon lay in a term the white people had been warning the locals about: deforestation. Yes, the politicians and wealthy businessmen were stripping the land bare of its natural cover for the lucrative timber business. Environmental rape on a large scale. He let out a sigh and hopped into his truck. His job here was done. He hoped that one day Kabala’s spirits would come back and green vegetation would coat the land once more.

“Cloud seeding is the only way we can help those locals and save them from starvation.”

“We have told government officials about the dangers of cutting down trees for wood a lot.”

“Yes, John, I know, but it is the local people that suffer the consequences of the ingordigiousness of their politicians. We have to do what we can to help them.”

“You make a good point, George. After all, that is what this NGO was set up for. OK, let us request some drones and silver iodide from headquarters.”

John and George were two middle-aged white men who had made their fortune a long time ago in the British stock market. They had retired early and set up an NGO called RDM-Rain Dance Movement. It was their goal to bring rain to places in Africa that didn’t get enough of it because of global warming. They had named their NGO the “rain dance movement” to make it more culturally friendly due to the beliefs that certain African tribes held that a particular type of dance could peel open the clouds and please the rain gods to let flow their showers. They used a method called “cloud seeding” to modify the structure of the clouds and increase the chances of precipitation.

Crickets chirped, and leaves rustled. The night breeze blew through the surroundings, while the moonlight created shadows. Morlai tossed and turned in his hackneyed grass bed. A lot was on his mind, but more so the deplorable state of his village. The supplies Pa Thomas had brought earlier today were barely enough to be shared among all the inhabitants of the village. His stomach rumbled as if to remind him of its empty state. He had given his own ration of food to his wife and children instead. Something had to be done, and fast. He came from a long line of revered rain dancers, but the art had faded into myth over the years, and there was no need for it, until now. Tomorrow, he would start his journey to reclaim the lost art.

“You must be joking. The art of the rain dance vanished years ago. Do not waste my time.” Chief Santigie yelled angrily at Morlai.

“This is the only chance we have, sir. The village is suffering. I can invoke the spirits of my ancestors, bring the rain back, and bring our spirits back.”

“My friend, if you want to go along with your folly, go ahead with it. I don’t know why it is you are bothering me with this.”

“For your permission, sir, in order to prepare for this, and for the dance to be successful, it must be witnessed by the entire village. I would need your drummers to play me the tunes of old.”

“Just do what you want, and tell me when you’re ready. I have nothing to lose in any way. Now leave me be.”

“Yes, Sir,” Morlai replied gently and exited the chief’s hut with a bow.

Just as he was about to leave, he noticed clouds of dust in the distance, approaching at a fast pace. A white vehicle, coated with a thin layer of red dust, parked just outside the chief’s hut. Two middle-aged white men jumped out of the car, accompanied by their driver. The men looked around the village, taking everything in with their eyes. What could they be doing here? Morlai wondered to himself. Chief Santigie uncharacteristically darted out to meet the men. The proud chief, who rarely left his seat and commanded everyone to bow before him, was now rushing out to meet people because they were white. Morlai let out a hiss. He hated the men already. He stood quietly in the background and listened to the conversation between the men and the chief.

“Chief Santigie, we are happy to finally meet you in person. We have heard a lot about you and your village from the district officer, Sajor.”

“Ah Sajor, he is a great friend to me. How may I help you, sir? Is there anything I can do for you?”

“We have an NGO called Rain Dance Movement, and what we do is bring rain to impoverished areas that need it badly. We then try to educate the people on how to take better care of the environment. Sajor reached out to us a month ago and told us how grave your situation is, but on the drive here we have seen that it is worse than we imagined.”

“Rain dance, you say? We have something like that, but rain dances have not been effective for years now. In fact, one week from now, we would hold a rain dancing ceremony, you are welcome to come and see it. We would very much like your help. When would you like to start?”

“We would like to start next week without delay, and sure we look forward to seeing an actual rain dance ceremony, we have heard a lot about them.”

Morlai listened to the conversation with disdain. How dare they make a mockery of the sacred rain dance art. He watched as the white men shook hands with the chief, got back into their vehicles, and drove away. The chief saw him staring and said, “The white people will do it better. You know, white men have sense. However, I will still call out the people and my drummers for you next week. A chief always keeps his word.” Morlai thanked him profusely, bowed, and walked away. He had work to do.

The forest was always calm during the day. Sun rays filtered through the dried leaves and hit the ground at various angles. The forest was a dull brown shade, a mere depressing shadow of what it once was, before it was thick with foliage, and its hue was a vibrant dark green shade. Now it was like a bald, withered old man. The only life forms were a few insects here and there, and brown lizards scurrying across the path. Most of the trees and shrubs had dried up. The leaves crunched and rustled under his bare feet as he walked. He soon reached his destination, a derelict hut with a few bony chickens out front pecking at the dirt. He was looking for Pa Sanfa. If anyone had an idea of the rain dance, it would be him. There was no sign of the old man. He kept looking around, till he heard movement behind him. Pa Sanfa had changed over the years, and time visibly showed on him. He was permanently bent over and used a stick to support himself. His face and body were riddled with scars and wrinkles like road networks on a map. His skin hung loosely on his body and flapped against sharp protruding bones.

“My son, I haven’t seen you in quite a while. You still remind me of your grandfather. You are the spitting image of him. How can I help you? Surely you didn’t come all this way, after all these years, just to check on a lonely old man like me.” Pa Sanfa’s voice was so clear and gruff that Morlai was startled. It had a youthful vigour that belied the battered appearance of its vessel.

“I come from a lineage of rain dancers. Their blood runs through mine. With the current state of the village, I have to do something. I need you to teach me the lost art of the rain dance.”

“All these years ago, I was waiting for you to ask me. Yes, I will teach you.”

“Place your feet apart like this, take a deep breath, clear your mind, connect with your ancestors, connect with nature, be one with your environment. Picture yourself as a conduit of nature’s raw energy; let it flow through you.” Pa Sanfa said as he maintained a similar stance in front of Morlai. He adjusted the direction of his hands, turned his palms inside out, and corrected the distance between his wide-open legs. He flowed and moved with him, teaching him to listen to nature, teaching him to move his body to her orchestra. The rain dance was more than an art form; it was surreal and therapeutic.

Morlai continued the lessons with Pa Sanfa daily, from sun up to sundown. He taught him the names of the different clouds in the sky and the names of the different types of wind. He taught him control, poise, how to move his body like water, and how to sense, smell, hear and see with his eyes closed. By the time it was the last day of the week, Pa Sanfa was quite pleased with him. “Great son of Morlai Kpanga, you have done well. Your grandfather would be proud. Tomorrow you will no doubt bring rain back to Kabala. Go home and rest. You have a big day tomorrow.” Pa Sanfa said contentedly. On his walk home, Morlai could hear a buzzing sound coming from an object in the sky. He squinted at it. It was shaped like a flying squirrel with no tail. It buzzed and moved in a straight line. He wiped his eyes and stared again. The strange flying object had disappeared. It was probably just the sun playing tricks on his eye, so he paid it no mind.

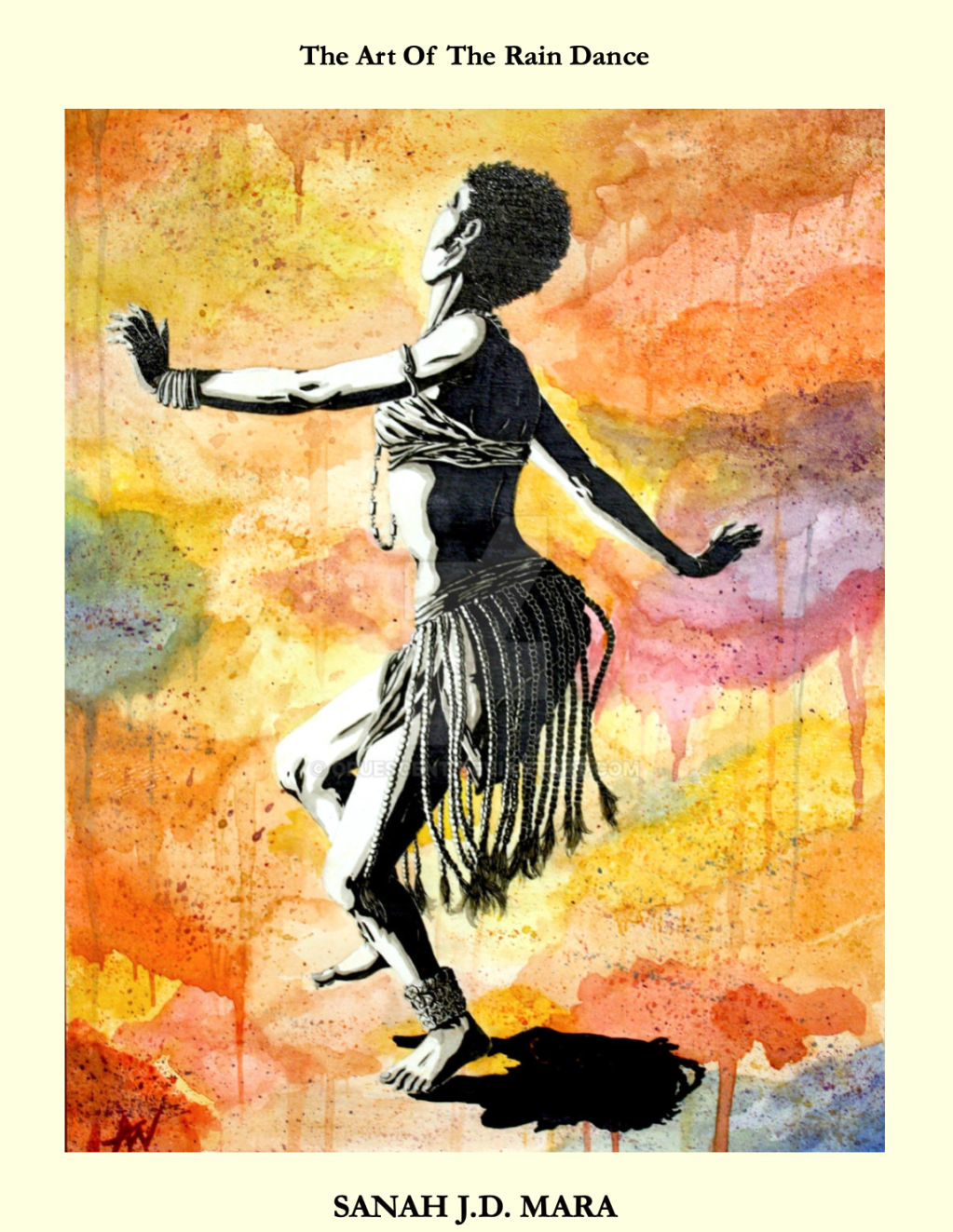

Morlai walked into the village centre proudly. He was dressed in a dark brown garment, with brightly coloured feathers and cowrie shells adorning his head, elbows, and ankles. A single red cloth was tied around his midsection, and with each movement, the cowries rattled and vibrated, emitting a tinkling sound. The entire village was out, every man, woman, and child. The chief sat in his chair with a stern face, accompanied by the white men, one on each side of him. The drummers were dressed in only a single white cloth wrapped around their waist, their upper bodies left bare for all to see. They pounded on their huge drums with their hands, striking the dried animal skin cover at different angles. It was a thunderous sound.

As Morlai walked into the middle, head held high, he felt regal. With his head bowed and his palms clasped, he jumped high into the air and landed on all fours like a cat. The crowd went silent. His heart pounded in synch with the drums. Slowly, he unfolded his limbs like a spider playing dead, and he stood tall once more. With his big toe, he drew a circle in the dirt and started moving his body like a snake. With outstretched palms and his lower body spread out in a straight line, he swayed and glided across the earth as Pa Sanfa had taught him. It was time. With a few more deft, exaggerated movements, he sang the sacred incantations at the top of his voice, “Uti futi la ta ta, ta ta la futi uti, Kanu masala, Kanu masala.” He opened his eyes and stared at the heavens. Nothing. The clouds were the same, no rain poured down. He looked around at the crowd, panicking. The chief still had a stern expression on his face. Even the white men just stared at him quizzically. Only Pa Sanfa made a signal to him to try again.

He tried again, his movements were more exaggerated than before. Alas, his efforts were wasted; the result was the same, no rain. The crowd was growing restless and annoyed. Audible murmurs of discontent could be heard. Even the drummers hit the drums with less enthusiasm than they had at the start. Morlai decided to give it a go for the third and final time. He moved and danced as he had never before. He emptied his mind totally, his only focus being the rain. He chanted the incantations as loud as he could, till his voice gave out. He leapt high into the air, landed with a twirl, and opened his hands wide apart, with his head facing the heavens. His eyes remained closed. He felt something cool on his forehead. Rain? No, it was just a bead of sweat. He hung his head in shame. The crowd started to disperse with loud hisses of dissatisfaction. The chief turned his back to him and walked away with the white men. Only Pa Sanfa came over to him and draped his frail, bony hand across his shoulder to comfort him.

That was when they heard it. At first, low rumbles, then a loud growl, like a lion’s roar, The sun dimmed, as it was covered by a thick, fluffy, dark cloud. Then, without warning, it poured, in drops at first, then in heavy showers, rain, rain. It rained. For the first time in years, it was raining in Kabala. The showers beat the earth, and the scent of petrichor teased Morlai’s nostrils. He jumped and shouted, rejoicing that he had done it! Pa Sanfa hugged him tightly. The villagers all came back and hoisted him on their shoulders. The chief looked at him with admiration and gave him a nod of respect. The white men stood there in the rain, but they didn’t seem surprised, rather they just smiled at him.

“Why didn’t you tell him?”

“Tell him and rain on his parade,” John said, chuckling at his poor joke attempt. “The poor fellow looked so devastated when he didn’t succeed on the third attempt of his rain dance.”

“He did look rather happy in the end.”

“Exactly, George; I didn’t want to spoil his mood, and the people around here need hope.”

“I see what you mean, John, but we really need to explain to them that it was because of the drones that had been deploying silver iodide into the clouds all these days that they had been able to see the first drops of rain in years.”

“We will tell them, I have a plan in place. Let the young man enjoy his victory today. Let us not ruin his mood and his reputation. Sometimes all people need is hope and a belief in the extraordinary. After all, I did rather enjoy the rain dance performance.”

The two men chuckled as they walked to their vehicle and drove off.

The next day, Morlai was sitting in the village square talking to a circle of star-struck children when the two white men from the previous day arrived in their vehicle and beckoned him over. What could they possibly want, he asked himself grudgingly. Nevertheless, he still walked over to hear what they had to say.

Hello, I’m George, and this is John. It is an honour to meet you. You left quite an impression on us with your rain dance the other day. ”

“Thank you, thank you.”

“Come into our vehicle and let us show you something.”

The two white men pulled out a strange familiar object and switched it on. It buzzed to life, sounding like a thousand wasps. The realisation hit Morlai’s face; this was the object he had seen the other day in the forest that looked like a flying squirrel. What was it? “It is called a drone.” One of the white men said as if they could hear his thoughts.

“We use these drones to disperse substances into the clouds that cause precipitation. However, this method, cloud seeding, has its negative effects. That’s why we need your help. People look up to you now. We need you to sensitise them to the dangers of cutting down trees without growing them back. We need you to help us help them look after their environment better so they do not suffer from such drastic droughts again. “

“I understand. We will work together. Thank you for not outing me.”

Morlai shook hands with the white men and walked away. The future was bright; he had found his purpose. He would teach rain dance to kids to keep the culture intact, and he would also advocate for people to look after their environment better. It was the perfect blend of the old and the new.

Elsewhere, on the surface of Lake Sonfon, a multicoloured bird bathed on the surface of the lake, a bird that hadn’t been there in a while. Nature was beautiful, the creatures were already returning, and the spirits were back from vacation it seemed. All it took was the art of the rain dance on nature’s grand stage to bring together its design once more.